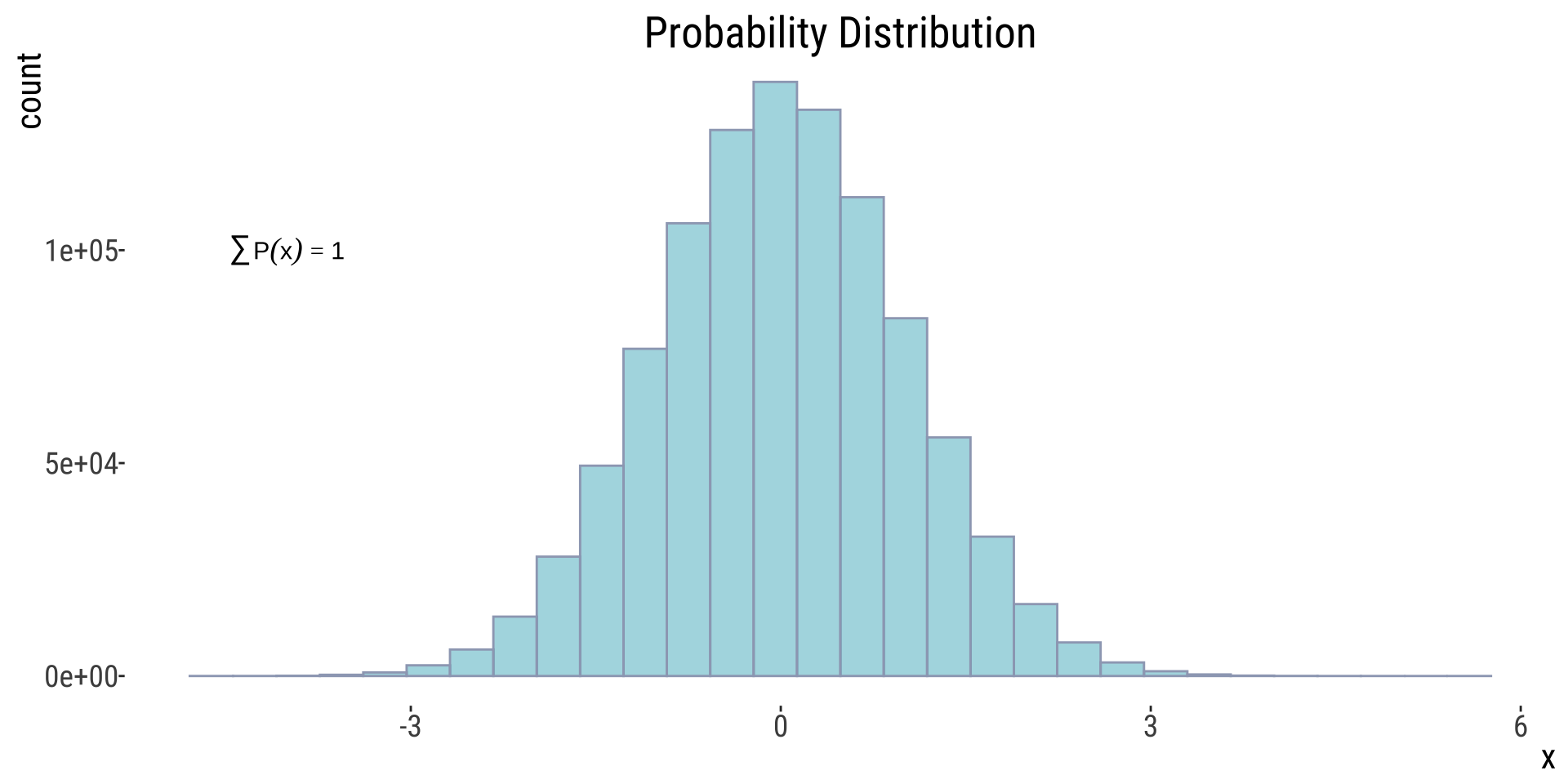

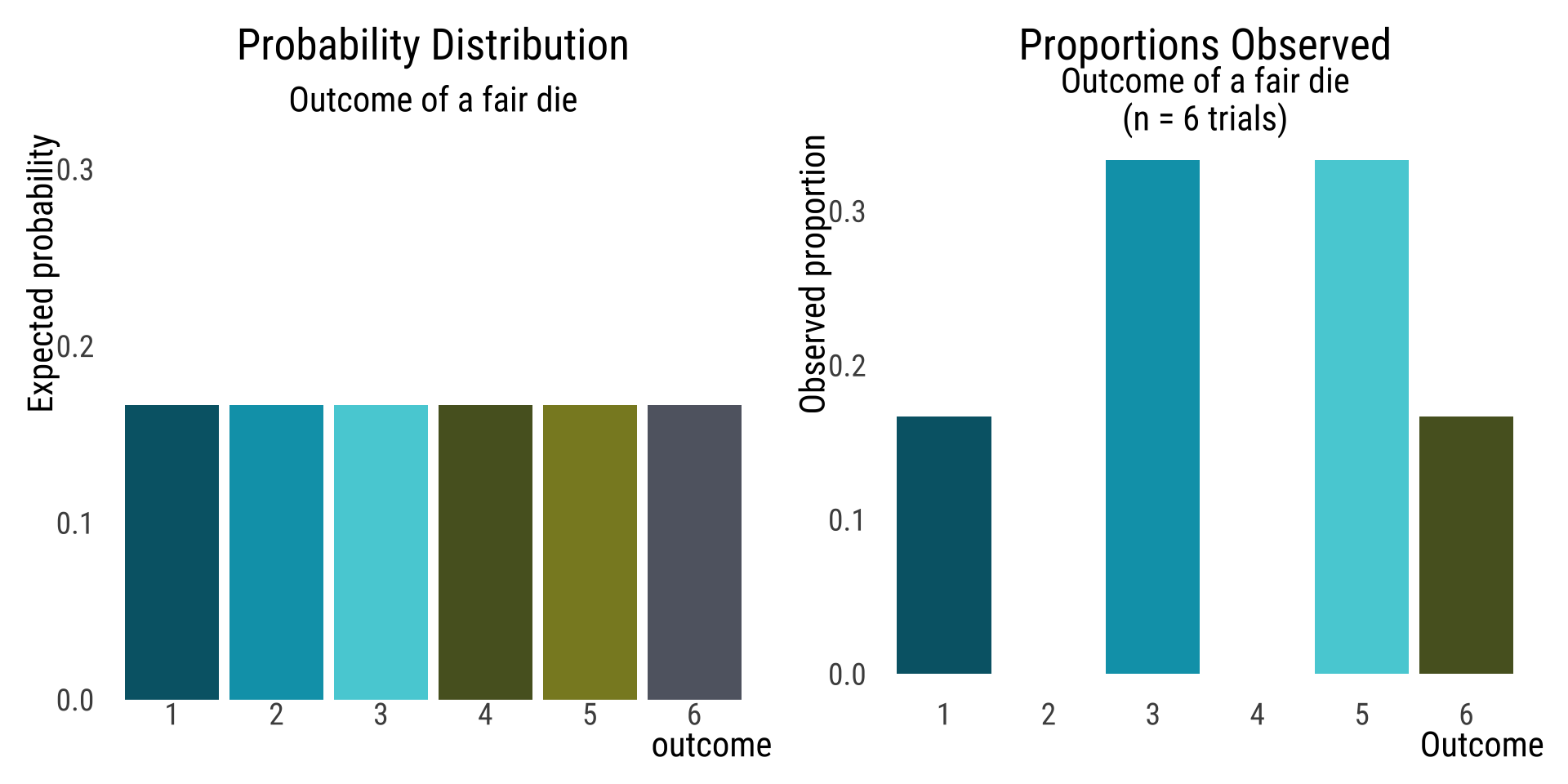

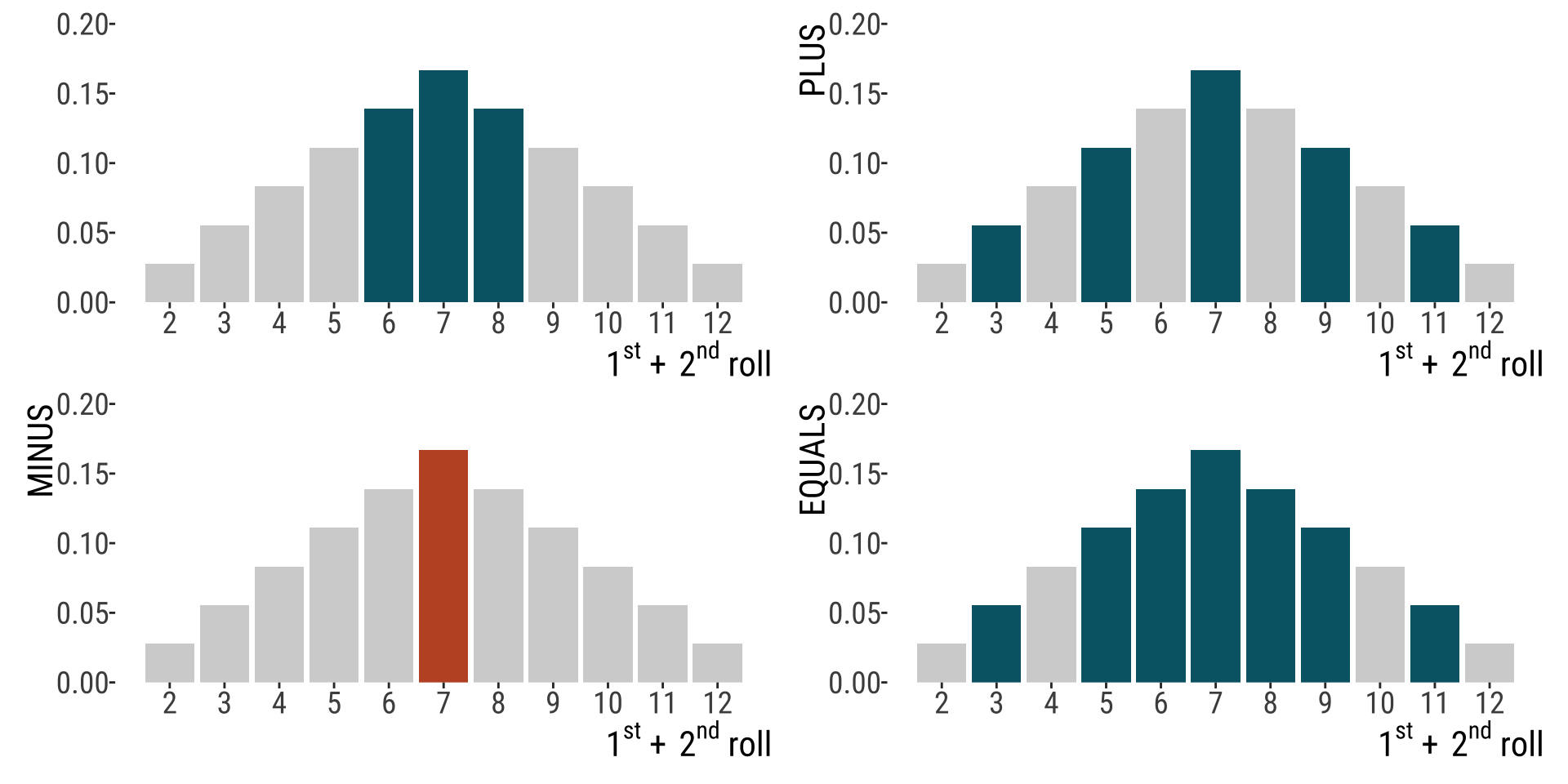

two.die.revisited <- data.frame(

Outcome = c(2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12),

prob = c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1) / 36) |>

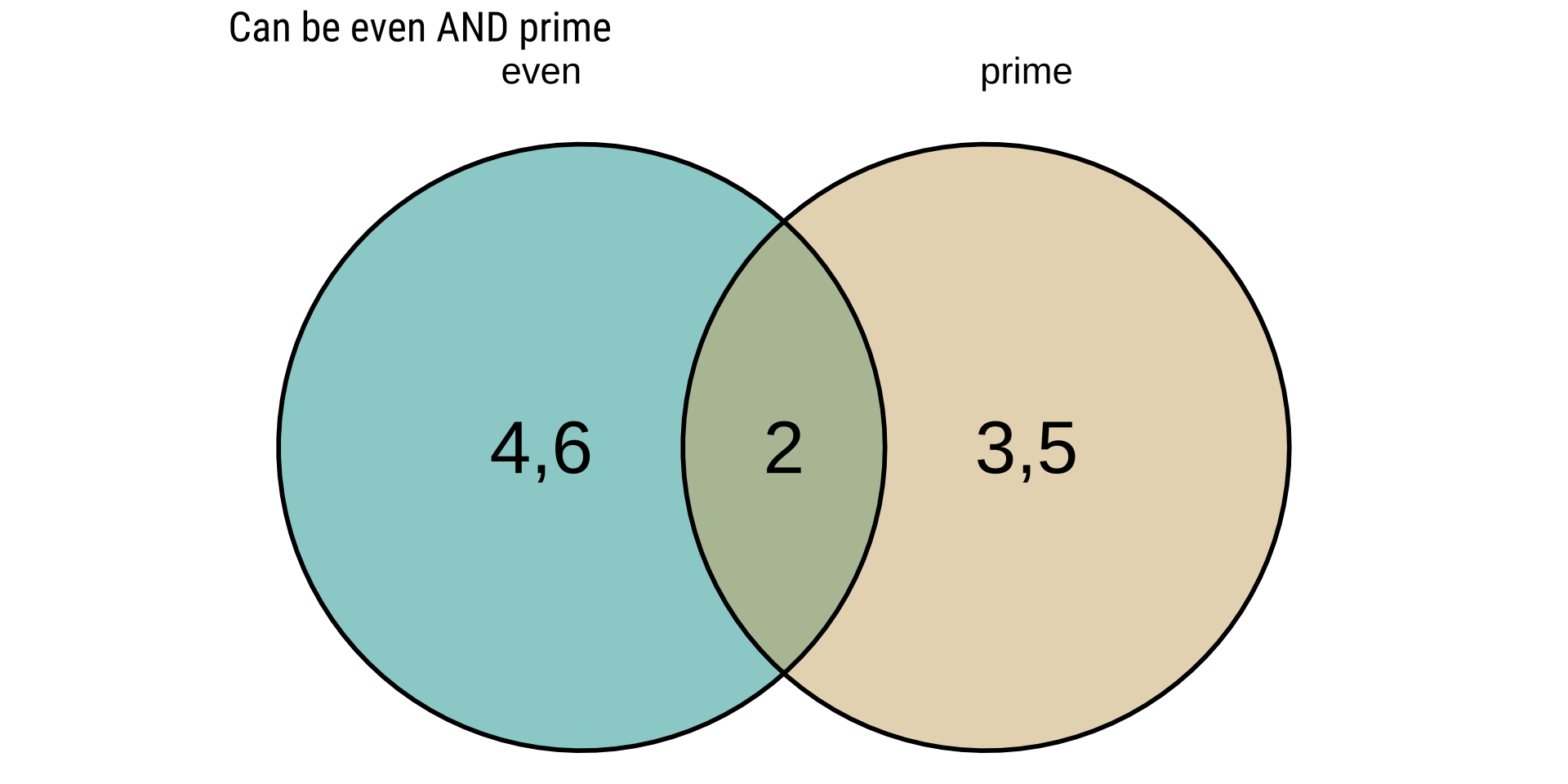

mutate(sixeight = Outcome >5 & Outcome <9,

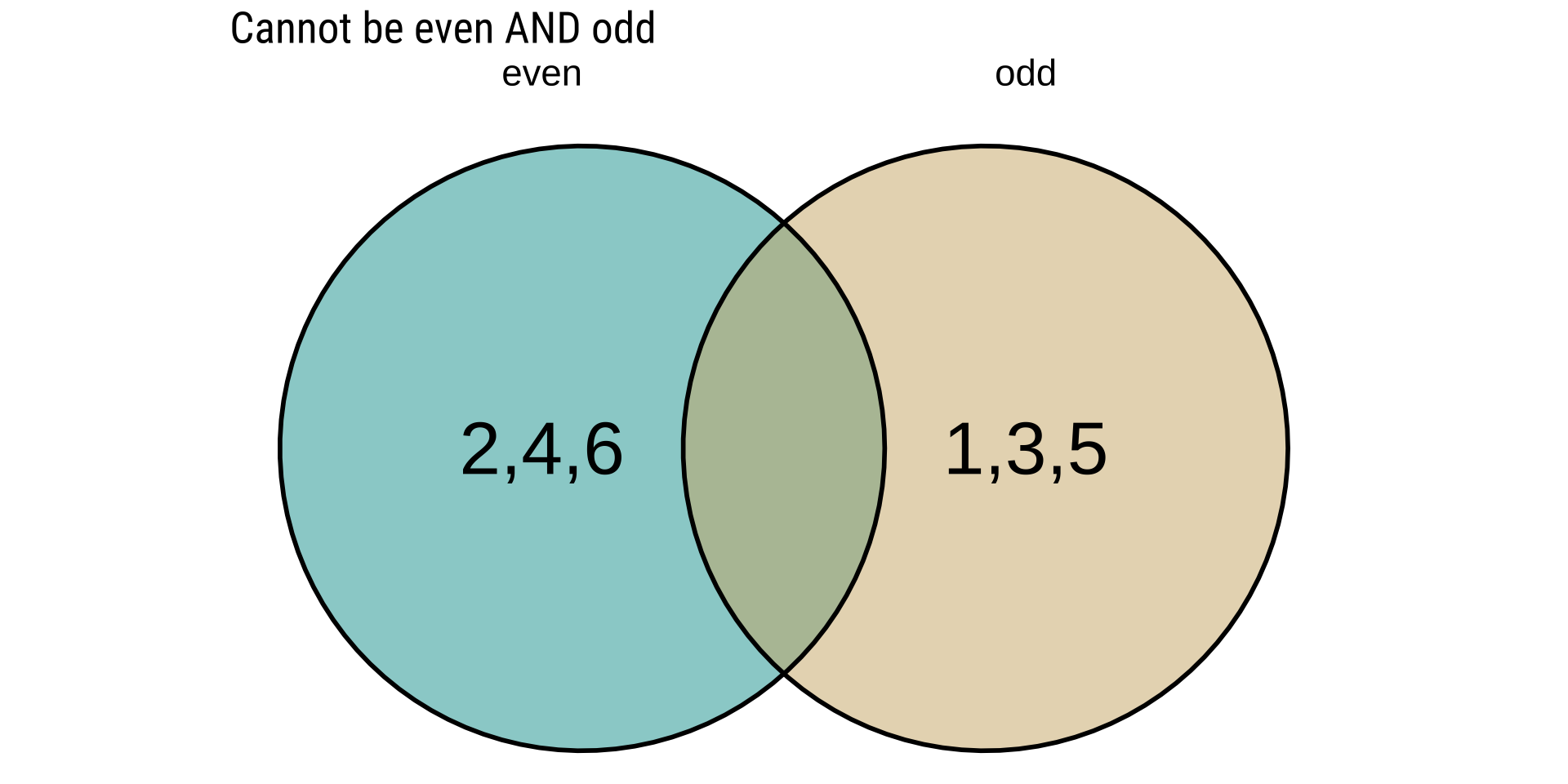

odd = Outcome %%2 ==1,

oddandsixeight = sixeight & odd,

oddorsixeight = sixeight|odd)

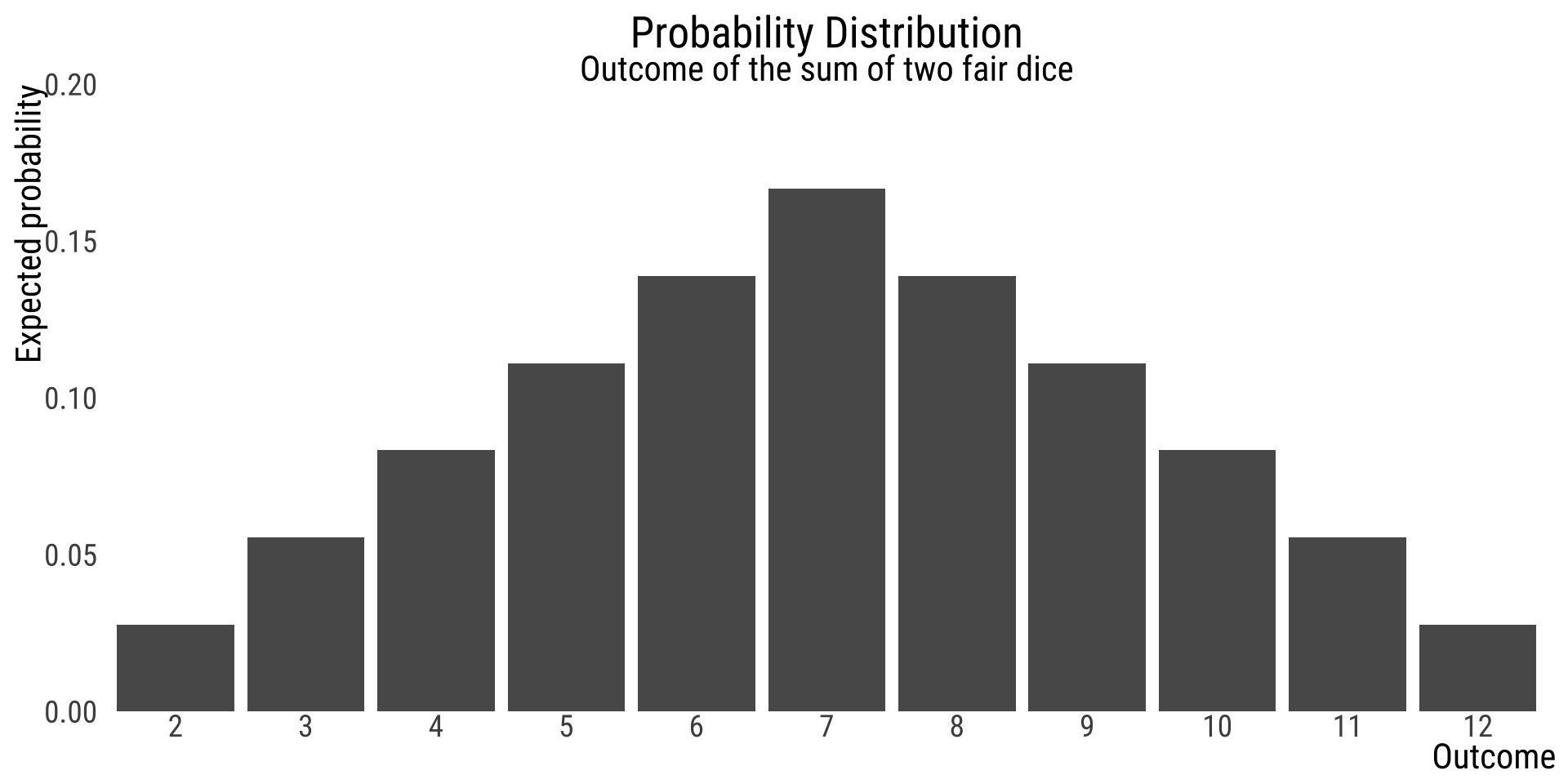

dice.theme <- ggplot(two.die.revisited, aes(x = Outcome, y = prob)) +

ylab("")+

scale_y_continuous(expand = c(0,0), limits = c(0,.2))+

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:12) +

bb_theme() +

xlab(bquote(1^{st}~+~2^{nd}~roll))

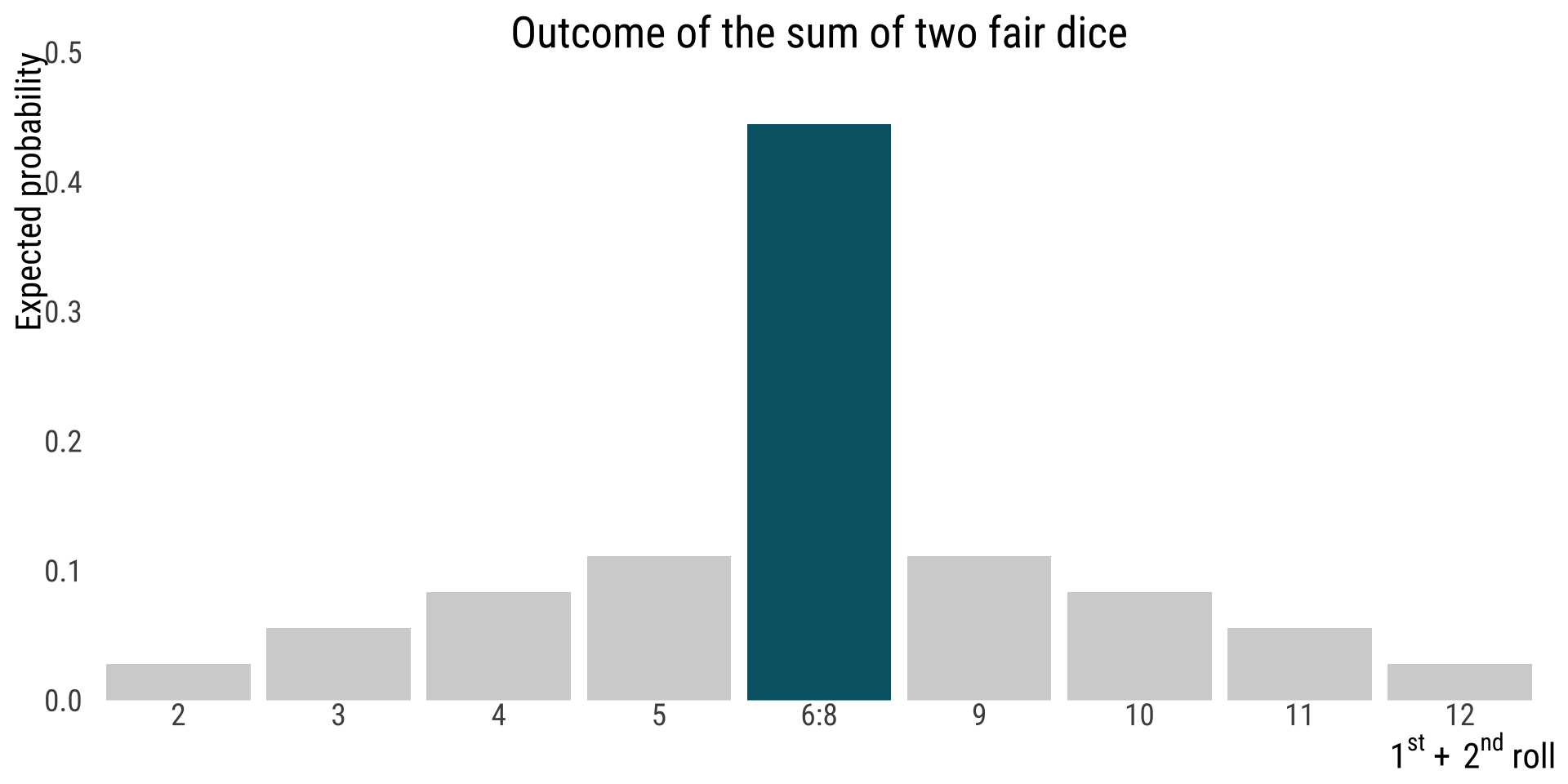

sixthrougheight <- dice.theme +

geom_bar(aes(fill = sixeight),stat = "identity",show.legend = FALSE) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightgray","#006475"))

odd <- dice.theme +

geom_bar(aes(fill = odd),stat = "identity",show.legend = FALSE) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightgray","#006475"))+

ylab("PLUS")

seven <- dice.theme +

geom_bar(aes(fill = oddandsixeight),stat = "identity",show.legend = FALSE) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightgray","#C0532B"))+

ylab("MINUS")

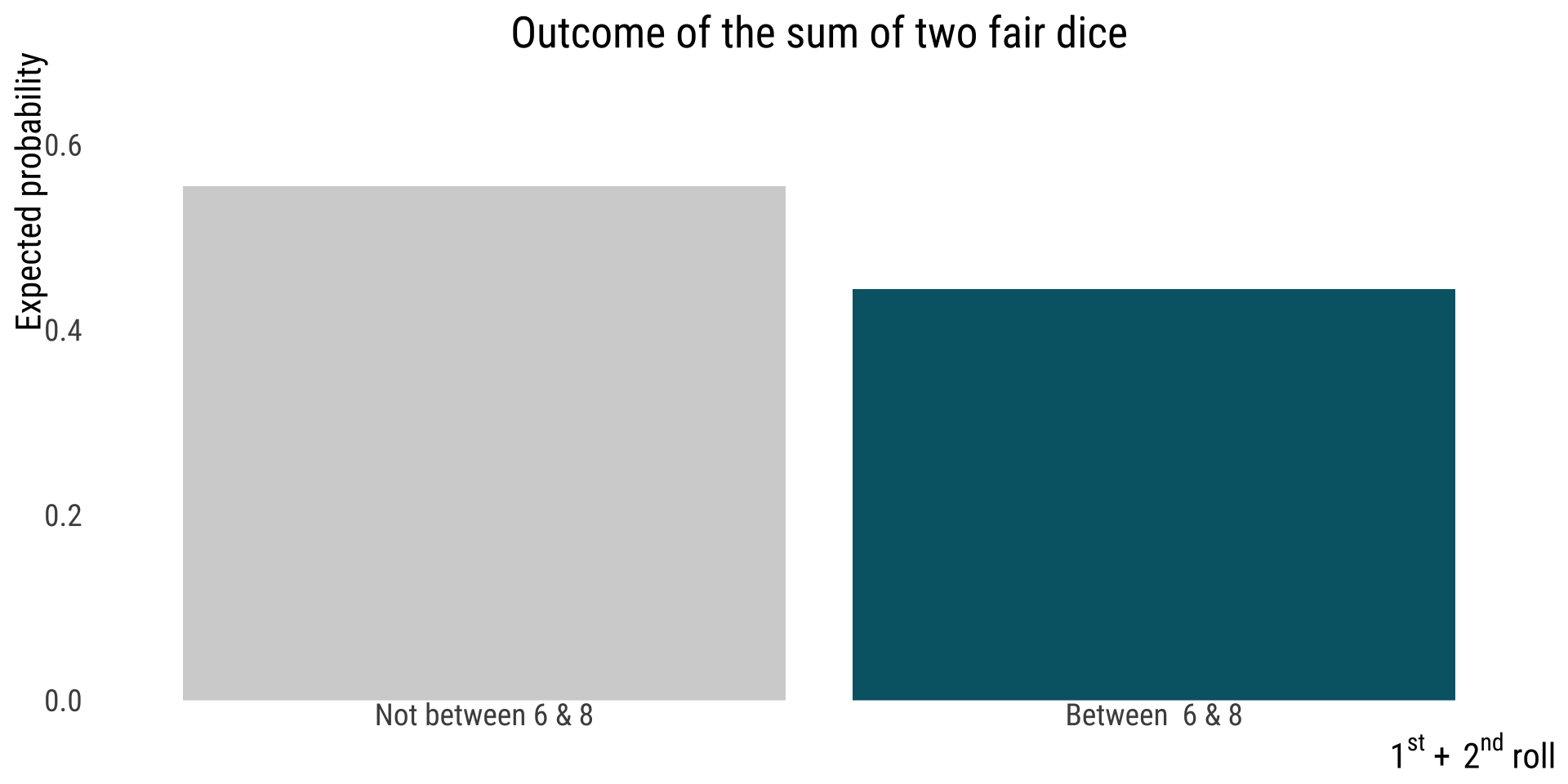

tots <- dice.theme +

geom_bar(aes(fill = oddorsixeight),

stat = "identity",show.legend = FALSE) + scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightgray","#006475"))+

ylab("EQUALS")

library(patchwork)

sixthrougheight+ odd+ seven+ tots